みなさん、こんにちは!

A week back, one of my seniors published a series of three CTF challenges from Cryptography, Reversing, and Forensics. This write-up focuses on the Reversing challenge.

First look at the Binary

I always like to perform some easy tests on the binary which can be a easy win or at least give insight to what’s going on inside without having to delve deeper for now.

I ran the file command to see the information about the binary, it displayed the following:

One thing I noticed is that the Binary is “not stripped” which means we can debug it easily and disassemble the functions easily in a debugger, in other words, it’s not obfuscated here.

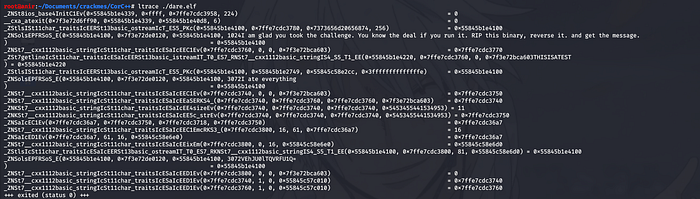

The next commands I run are the basic, ltrace, strace and rabin2 -z :

It is now obvious from the ltrace output that the binary is written in C++ language because a binary written in C language would never produce an output like this. Notice the _ZNSt7__cxx which actually is a function indication in C++.

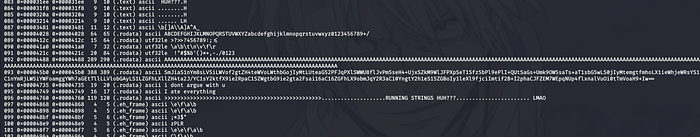

Running rabin2 -z sure returned an interesting result:

We are greeted with some very interesting strings and a string mocking us with “…RUNNING STRINGS HUH???…”. Also a notice a Base64 type of string in there. I immediately try to decode it had unreadable characters so, nope it’ll not be that easy win. Omoshiroi!!

Taking apart the Binary

“Now its time to bust you open!” — Accelerator (A certain scientific accelerator)

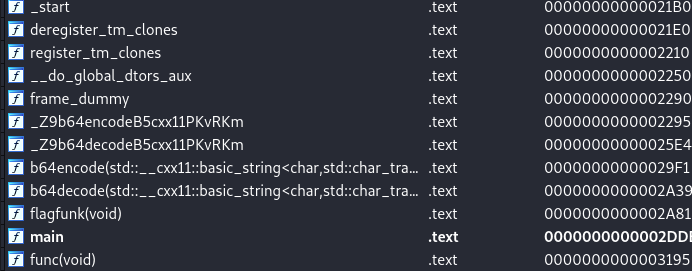

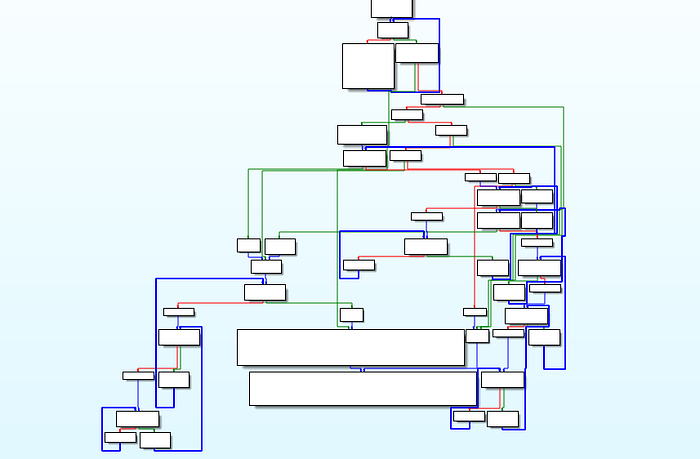

I opened the binary in IDA here’s how I made a roadmap myself:

Neglecting all the compiler-generated functions, we see two interesting functions, base64encode and base64decode and one super interesting function flagfunk(). Obviously our area of interest would be flagfunk().

One thing that is actually pretty comfortable in C and C++ binaries is that any outgoing functions always start from main so let’s inspect main and see if we can sketch a tree, as to where the program flow is directing too. In this way, we can ignore unimportant functions and focus on fishing out the flag.

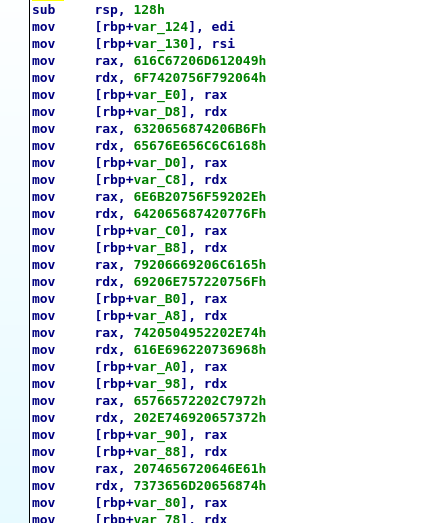

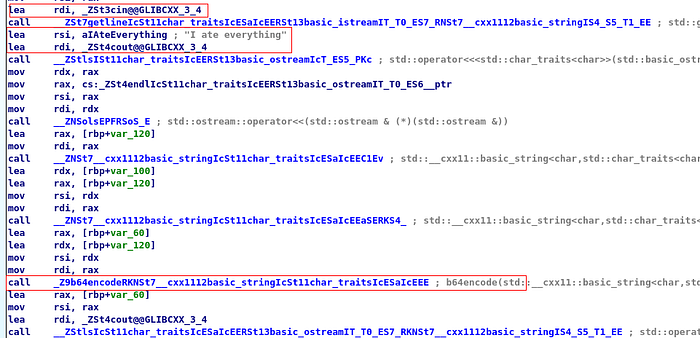

Upon inspecting the main, I found:

The welcoming message that we found while running the binary is actually encoded in the form of ASCII making it somewhat hard to actually spot input and output. This is a form of obfuscation.

This is by far the most interesting part of main()!! The program takes the input via cin (first red box) then immediately displays, “I ate everything” (second red box). Then it sends the string as an argument to b64encode ( third red box). B64encode function returns a b64encoded string of the input and then it is printed out on the screen via cout (the last lea to the cout). Upon running the actual binary with dummy inputs fetch the same result. Other than this call to b64encode, there is no other call to any other function in the binary.

At this point, it’s better to think of patching or jumping to any uncalled functions which contain the flag. We found a strange base64 string in the strings too and there is a base64 decode function too! But decoding that base64 string online didn’t do anything well. So it maybe is possible that the algorithm of base64decode has been altered specifically for this string. That is however unlikely since I didn’t find any unusual things in the said function.

So the main function is pretty much useless. I pay a visit to the func(void)

After spending a lot of time analyzing the “func()” function I realized it was a trap. Under certain command-line argument conditions, it can be called from main to display certain messages. We’ll get to that later but other than that it does not do anything with the flag or the base64 string I found earlier in the strings dump.

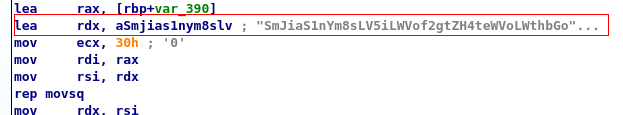

With all these out of the way, I went to the promising “flagfunk()” function and yes it had exactly what I wanted it to have! It calls the base64decode function and it loads into address the base64 string we found earlier. It’s all coming together!

Since now it is clear that:

- flagfunk() is calling the decode function with the string as an argument.

- The decoded string is being returned to the flagfunk() function

- Some sort of operation is being done on the decoded string to generate a flag. So at this point, it seemed feasible to just call the

flagfunk()function!

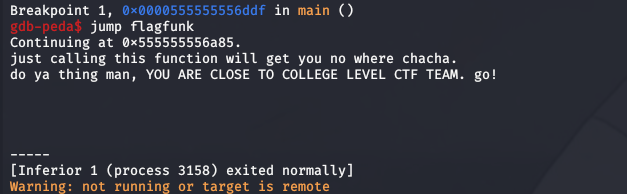

I did that but…

I break at main, run the program, and then used the gdb command jump to directly control the RIP to flagfunk() but this is what I got. Just before the supposed flag is to be printed, it waited until the user exited the program.

Dynamic Analysis!

The binary is a non stripped version so, we have two options: either analyze and recreate your own version of flagfunk() to generate the flag or we can simply run dynamic analysis and see the flag being generated! I chose the second option since it is easier!

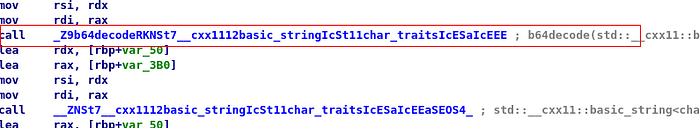

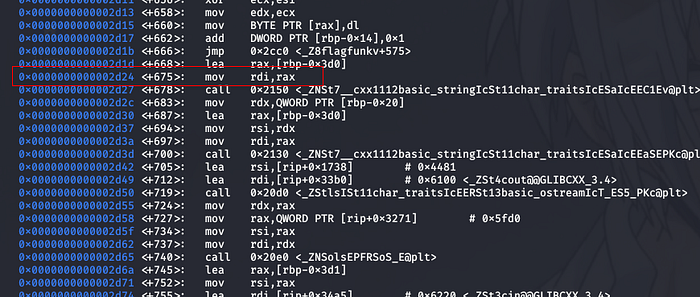

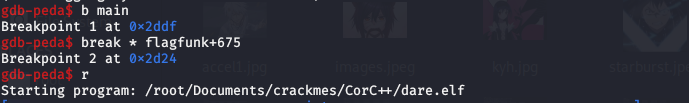

We have to choose to place our breakpoints very carefully since it would determine which position of the flag generation we are at:

I chose the marked break-point since the program doesn’t seem to be doing anything special after that.

There is however a little trick: Simply jumping to the flagfunk() won’t do and we won’t be able to get to our desired vantage point to observe things. We need to place a break-point so that the execution gets halted at that point.

The whole point of breakpoints is actually issuing an interrupt (\xCC).

Now we just need to run and when it halts at main+1 execute a jump instruction to flagfunk().

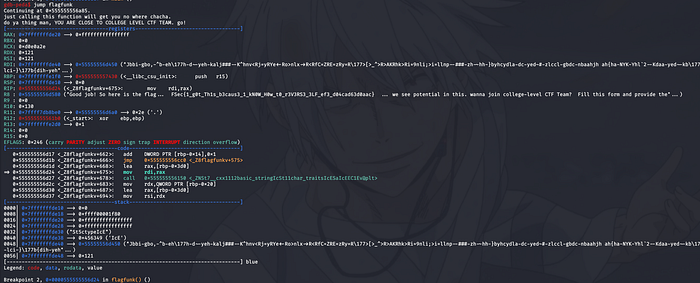

Here I go! STARBURST STREAM !!

The flag is already visible but hey, its cut in way so to view full simply use x/10s $r8 which basically prints the next 10 addresses referred by the register R8

Got it!: The whole string is

“Good job! So here is the flag… FSec{1_g0t_Th1s_b3caus3_1_kN0W_H0w_t0_r3V3RS3_3LF_ef3_d04cad63d0aac} … we see potential in this. wanna join a college-level CTF Team? Fill this form and provide the above flag we will recognize you next time. https://forms.gle/HiN6UGg8GusQjgXc7 Cheers.”

flagfunk()

So, we got the flag noice! But what magic went in flagfunk() that an unreadable string got suddenly converted into a readable flag?

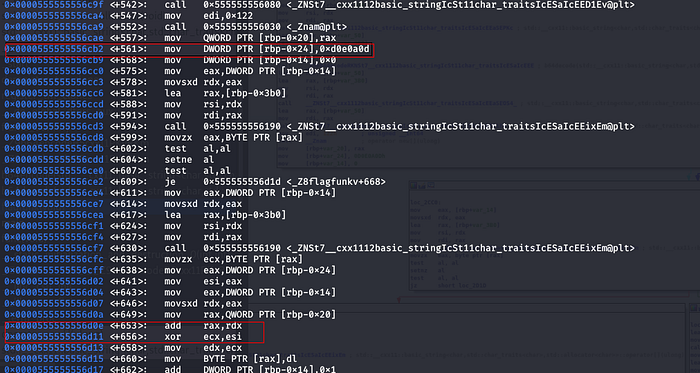

Here I think is really what’s going on:

A strange hex string “0xd0e0a0d” into the memory and a lot of loops were operating here. So I think maybe the decoded string was formatted and ANDed and XORed with this string.

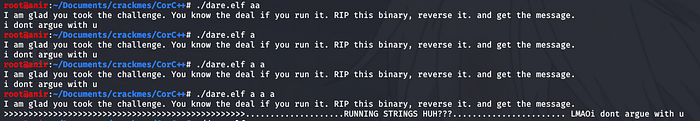

Playing with input

It’s time to talk about the func() function. I realized that certain inputs can trigger the call to this function from main.

So we see, func() function is called under certain circumstances from main.

Conclusion

Interesting binary! It reminded me that sometimes things have an easy workaround too!

This article is written by Anirban Chakraborty and Taken from This Medium Post by the author hence do not comes under Peer Review Policy. To check the profile of every writer of FrigidSec-Blog please visit HERE